Over the past ten days, Japan’s decision to release treated nuclear water has ignited waves of anger and concern on Chinese social media platforms. Many netizens express worries about how the Fukushima wastewater might impact the marine ecosystem, while others are deeply concerned about the long-term repercussions of this pollution on their food safety and overall well-being in the coming decades.

The huge public concern over the Fukushima water seemingly poses a stark contrast with that over climate change. As Miranda Barnes recently noted in our Weibo Watch newsletter, the urgent implications of climate change and global warming caused by human activities are a huge topic of debate in Western countries, especially in relation to extreme weather. In China however, the phenomenon of “eco-anxiety” doesn’t resonate among the public in the same manner as it does in Western discourse, despite notable events like China recording historically high temperatures in July, the impact of Typhoon Doksuri, last summer’s wildfires and this summer’s devastating floods.

In a recent Reuters article about the discussions surrounding climate change in China, a Greenpeace senior adviser called it a “big missed opportunity” that Chinese state media and official channels did not connect the recent extreme weather in the country to its own carbon emissions and climate change at large.

China’s limited engagement with the climate change discourse is also noticeable in the realm of social media. Researchers Chuxuan Liu and Jeremy Lee Wallace published a study about “China’s missing climate change debate” (2023), concluding that social media site Weibo does not have very active discussions about the topic of climate change at all. They found that only 0.12% of the unique trending topics on Weibo from June 2017 to February 2021 were related to this theme.

Some news articles suggest that the lack of climate crisis discussions in China relates to the challenges faced by grass-roots environmental movements in contemporary China, alongside censorship.

But climate anxiety is not the only form of eco-anxiety, and it would be a misconception to assume that absence of panic over climate issues means that Chinese people are not concerned about the environment or the well-being of future generations at all. As explained in Eco-Anxiety and Pandemic Distress, various global threats, including climate change, ecological challenges, and pandemics, are interconnected in multiple ways. Pandemics can influence ecological problems, for example, and ecological dynamics and climate factors can also cause outbreaks and shape pandemics (Pihkala 2023, 1).

Climate change, global warming, and environmental activism may not hold as prominent a place in daily social life and online media in China as in the West, but some topics related to global ecological challenges — often communicated by state media and amplified by public responses — actually garner more engagement than in Western countries.

We delve into a few examples in this article. Given the scope of our discussion, we won’t go into the scientific details behind these phenomena; instead, we’ll center our attention on the public anxiety surrounding them.

Public Panic over Fukushima

Japan’s decision to start discharging treated nuclear water into the Pacific has already become one of the biggest topics on Chinese social media this year. Through Weibo posts, short videos, articles, and memes, people vociferously criticized Japan for what they saw as an irresponsible act of releasing “contaminated water” (污染水) – a concept popularized by official channels highlighting the toxicity of the disposed water, as opposed to the more neutral “treated water” (废水) term.

In the first days surrounding the Fukushima waste water release, a trending topic on Chinese social media highlighted how the move would harm to the oceanic ecosystem, with many people posting photos of dolphins, sealions, whales, fish, and other wildlife that could be affected by water pollution alongside the hashtag “History Won’t Forget.”

This post claimed that “the sea otters will also remember” what Japan has done.

In addition to a surge in anti-Japanese sentiments and concerns about the livelihoods of the Chinese fishing industry, another significant aspect of the viral online responses to the Fukushima wastewater issue has been the discussions regarding strategies for how to survive the perceived crisis.

While in the English-language media sphere, critics dismissed the panic as unwarranted, stressing that the disposal is well within safety limits or that environmental impact is negligible, the release of the treated water caused an outbreak of apocalyptic fears and many people immediately took action to protect themselves and their loved ones in various ways.

These fears are widespread, encompassing notions such as the contaminated water having the potential to induce mutations in marine life and elevate the risk of cancer when consumed by humans.

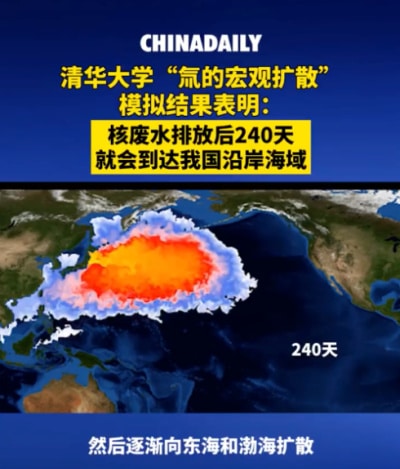

On the day preceding the wastewater release, Chinese state media outlet China Daily launched a hashtag about how “the nuclear-treated water will reach our seashore in 240 days” (#核废水排放后240天就会到达我国沿岸海域#). This statement was based on a Tsinghua University simulation study into how the tritium will spread.

A screenshot from the video posted by the Weibo account of China Daily about the simulation study, showing that the water will reach China’s seashore after 240 days.

The idea that the contaminated water discharged into the Pacific could reach China within less than eight months quickly gained traction on social media platforms, with many netizens reposting and highlighting the timeline, even planning their “last activities” within these days, such as consuming China-produced seafood or visiting the beach.

Rumors suggesting that the released water would reach the United States long after affecting China and nearby countries also gained widespread online popularity. Some of these analyses led to suspicions that the release of treated water must be a joint conspiracy by Japan and the United States, with the specific aim of targeting the lives of Chinese people.

Guidelines on how everyday practices could mitigate radioactive harm widely circulated. These included recommendations such as taking showers after it rains, identifying makeup products free from radioactive elements, or transitioning to a more vegetarian-based diet. Many of these tips, however, have no scientific basis. One restaurant in Shanghai even started offering anti-radioactive menus.

Meanwhile people began hoarding supplies in preparation for long-term survival. In the coastal city of Weihai, the closest Chinese city to South Korea, four tons of salt were sold in just one hour as citizens queued to stockpile salt on August 24. The salt frenzy stems from collective concerns about the impact of Fukushima water on food safety and that table salt – in the near future and in the decades to come – might also become compromised. There’s also a believe that salt might help in case of radiation pollution (iodized salt, however, is actually no antidote for radiation).

Although muck of the panic buying may have evoked memories of the past Covid years and preparations for the potential next lockdown, people actually also started hoarding salt back in 2011 shortly after the nuclear accident at Fukushima Daiichi in March of that year.

Russia’s Anthrax Outbreak

Similar to the Fukushima wastewater responses, the same question of “how long does it take to arrive in China” also frequently pops up in the discussions surrounding the spread of anthrax in Russia. Anthrax is a serious infectious disease that occurs naturally in soil and can cause severe diseases to both humans and animals.

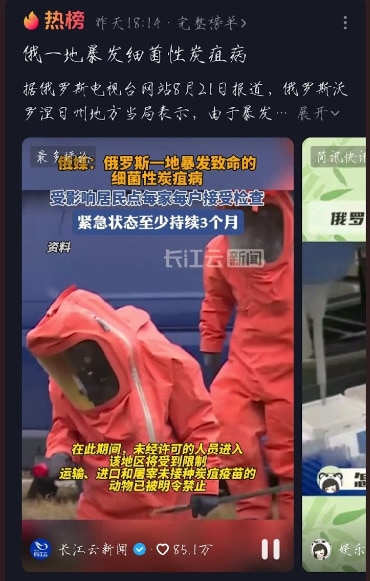

While Western media mostly focused on the Prigozhin jet crash incident, news of a mysterious anthrax outbreak in Russia (#俄罗斯一地暴发细菌性炭疽病#) has garnered attention on Chinese social media, causing significant concern. A current hypothesis directly connects climate change and the outbreak by suggesting that the thawing of frozen soil might have exposed people to decades-old infected reindeer carcasses.

A screenshot of the search result on Wechat channels on the topic of Russia’s anthrax, which shows that one related videos received 851,000 likes. Image shared by a netizen on Weibo.

In the comments under reports about the anthrax outbreak, many people are curious about how close the outbreak is to China’s borders. Others are researching anthrax transmission and fatality rates, wondering if it could turn into another global pandemic.

While most people are concerned about the outbreak’s potential impact, some are politicizing it without clear evidence, accusing the US of engaging in new “biological warfare” in Russia.

An image of the game “Resident Evil: Death Island” from a game review article.

The unease about Russia’s anthrax outbreak possibly being linked to “biological warfare” aligns with the public’s anxiety about mutations caused by Japan’s release of radioactive water. These worries amplify existing concerns about environmental changes, drawing parallels with the dystopian world of the Japanese survival horror game “Resident Evil,” where players face environments filled with zombies and other terrifying creatures. In discussions about the anthrax situation, a recurring question emerges: “Why does our reality increasingly resemble an apocalyptic survival game?”

Covid-19 Subvariants and Monkeypox

Apocalyptic game survival always becomes challenging when there are more than two crises unfolding at the same time. Beyond the concerns about contaminated water and anthrax outbreaks, another issue has captured the attention of the Chinese public recently – the spread of the latest Covid-19 subvariants, EG.5 and BA.2.86.

EG.5 is now the most prevalent in the US and has been detected in at least 52 countries. BA.2.86 is much less widespread, but scientists are alarmed by how many mutations it carries.

While more Chinese social media users are sharing their own experiences of getting Covid a third time, people begin to worry about the possible impact of a massive Covid-19 third wave, referred to as sān yáng (三阳). At the same time, some accounts are giving daily updates on new global cases of BA.2.86, and news reports related to new Covid sub-variants ignite strong reactions from netizens.

“Do not come over” meme used during the monkeypox outbreak.

We have seen similar responses related to news about monkeypox (mpox), with one domestic case of monkeypox occurring in July of this year becoming a top trending topic. Soon after, China saw the world’s fastest increase in cases of mpox, leading to significant concerns expressed by many, with people seeking information on preventive measures to avoid contracting the virus and expressing their hopes that the virus will remain far away from them.

Apocalyptic Games

“The main task is to stay alive”, concluded numerous netizens on Weibo after listing recent hashtags related to nuclear water, anthrax, and the next Covid-19 subvariant in their posts.

The combination of recent crises involving the environment and public health has made the prospect of impending catastrophe feel distressingly real to many. Half-jokingly, young people on Weibo express their concerns about having shorter lifespans. One netizen even humorously remarks, “Paying into your pension plan under these circumstances is almost like a form of romantic heroism,” suggesting that maintaining the belief that one will live long enough to enjoy their pension is overly optimistic and somewhat naive, especially in the face of present-day global challenges.

Beyond concerns about pension plans, a reluctance to have children has also emerged as a common sentiment, especially after Japan’s release of nuclear treated water. A viral screenshot of a street interview in Hong Kong captures the essence of this sentiment. In the interview, a young person nonchalantly responds that he isn’t worried about contamination of Japanese seafood because he doesn’t plan to have children. While not everyone shares this carefree attitude, many agree that having children in the current climate would be risky and senseless given the state of the world today.

A Weibo user sharing the screenshot of the interview on Weibo and comment that “[This is from] a street interview in Hong Kong. Some citizens said they did not worry about the contamination of Japanese seafood because they did not plan to have children.” The screenshot has now been censored.

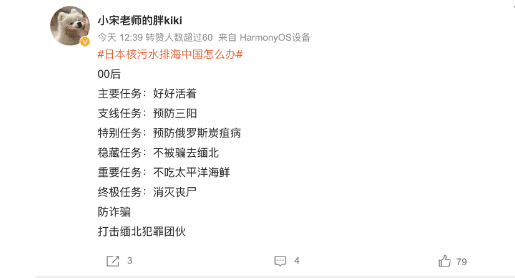

Some netizens humorously assume the roles of players in an apocalyptic survival game, assigning different tasks to themselves.

A Weibo user sharing their “tasks” in the survival game.

Under the hashtag ‘What China Can Do When Japan Releases Contaminated Water in the Ocean’ (#日本核污水排海中国怎么办#), one netizen outlines tasks for ‘players’ based on priorities: “Primary task: stay alive; Side-quest: prevent a third-time Covid-19 infection; Special Task: prevent Russia’s anthrax; Hidden task: avoid being deceived by North Myanmar; Important task: avoid consuming seafood from the Pacific Ocean; Final task: eliminate zombies.” Similar tasks have been listed in other posts, reflecting the sentiment that a mass extinction event is looming, making survival increasingly challenging.

Eco-Anxiety and a Bleak Future

While the term ‘eco-anxiety’ is familiar in Western societies and used by environmental activists, it has yet to become popular among the general public in mainland China, and there is no widely recognized Chinese translation for it. However, this doesn’t mean that only vocal activists are concerned about ecological disasters, or that ordinary people in China are indifferent to global challenges because their concerns are not framed in terms of climate change or expressed through activism.

As numerous studies have shown, ecological anxiety is not exclusive to the West. It’s just that the Western language and framework may have captured this mentality first, making it easy to overlook individuals in other regions who share the same sentiments but express them differently.

Certainly, as elsewhere, mainstream national media in China also contribute significantly to events and incidents that fuel “eco-anxiety” among the public. Moreover, changing political narratives play a pivotal role in shaping these dynamics.

In contrast to the West, Chinese media doesn’t necessarily connect global warming to the nation’s carbon emissions. A recent article published by The Economist discussed official and public discussions being “inward-looking” and avoiding direct engagement with climate change debates.

However, as recently pointed out by Miranda Barnes in our newsletter, additional factors contribute to the distinct responses of Chinese netizens, particularly regarding personal consumption and how individual behavior is connected to climate change. With many people, especially elderly, feeling they bear no responsibility for major pollution or gas emissions, “extreme weather” (“极端天气”) topics on on Chinese social media mostly center around personal safety, self-rescue strategies, and considerations for insurance rather than the collective responsibility of humanity for causing climate change.

Complicating matters further, the presence of low social trust and public skepticism towards official media exacerbates eco-anxiety and other concerns about well-being and the future. People often believe that prioritizing individual self-help and self-protection is the safer option, leading to behaviors like panic buying, even when official sources advise against hoarding.

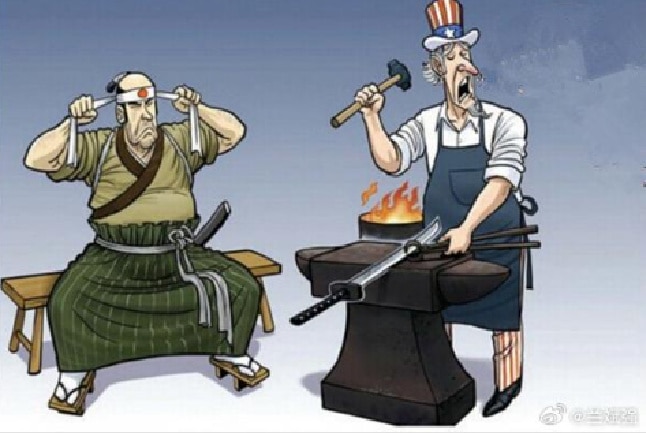

It is also noteworthy that many of the topics that people are concerned about when it comes to eco-anxiety and public health scares are linked, either directly or indirectly, to foreign countries. While several socio-historical factors contribute to these fears, there are critics who argue that Chinese leaders might exploit public sentiment against Japan or the US to deflect attention from their own internal economic, ecological, and political challenges. On the other hand, some Chinese commentators interpret the Western world’s apparent indifference to these issues as a prioritization of political strategies and capitalist profits over ecological concerns.

A cartoon posted on Weibo showing the US creating a samurai sword for Japan to fight with, mocking the US’s supportive attitude in Japan’s release of treated water.

Eco-anxiety is a collective response to various interconnected issues, including pandemics, disease spread, food security, environmental disasters, and the well-being of future generations. It’s like a complex puzzle where many pieces are intertwined, often involving intricate geopolitical and domestic political dimensions.

After the recent Fukushima fears, one person wrote on Weibo: “A while ago when listening to the BBC, I first heard the English term ‘eco-anxiety’ and I originally did not understand at all, why would people suffer from ‘eco-anxiety’? I hadn’t seen anyone around me with such emotions. But I get it now. I’m already deeply anxious myself.”

By Zilan Qian and Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Follow @whatsonweibo

References:

Liu, Chuxuan and Jeremy Wallace. 2023. “What’s Not Trending on Weibo: China’s Missing Climate Change Discourse.” Environmental Research Communications 5 (1).

Pihkala, Panu. 2023. “Introduction” In: Eco-Anxiety and Pandemic Distress. Edited by: Douglas A. Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Oxford University Press.

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

The post Beyond Climate Change Concerns: Fukushima Fear and Eco-Anxiety in China appeared first on What's on Weibo.