First published

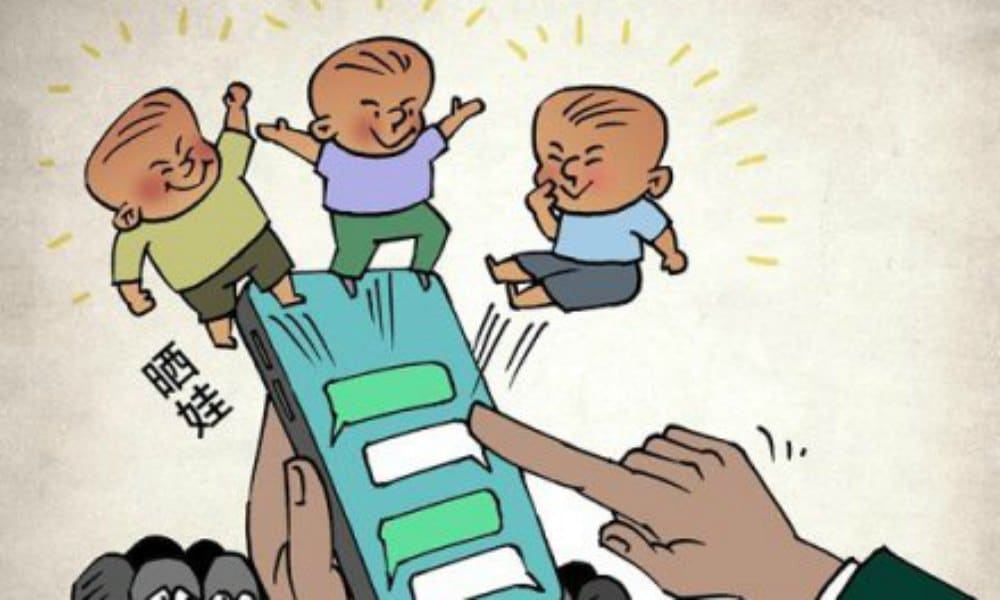

To what extent is it okay to post photos of your baby or children on social media, and when does it become too much? These questions are at the heart of a discussion that has been ongoing on Chinese social media recently, with the hashtag “Should You Be Sharenting on Moments?” (#朋友圈该不该晒娃#) receiving 140 million views on Weibo.

‘Moments’ is WeChat’s social-networking function, that allows users to share photos on their own feed that is visible to their friends, family, and other Wechat contacts.

‘Sharenting’ is a word that was coined to describe the overuse of social media by parents to share content based on their children. Around 2013/2014, the word came to be used more frequently in English-language mainstream media. In Chinese, the term for this phenomenon is ‘shài wá‘ (晒娃), which combines the characters for ‘exposing’ and ‘babies.’

Recently, more articles have popped up in Chinese media that take a critical stance towards parents sharing too much about their children on social media, with some WeChat Moments feeds consisting entirely of photos of children.

Sharenting Concerns

In English-language media and academic circles, the phenomenon of ‘sharenting’ has been a topic of discussion for years. In 2017, Blum-Ross and Livingstone published a study about the phenomenon, highlighting the concerns over it.

Some of these concerns are that ‘sharenting’ might infringe on children’s right to privacy, that it can be exploitative, is possibly exposing children to pedophiles, and might have consequences in terms of data-mining and facial recognition (110).

For parents, the reasons to share photos of their children online are multifold. It could just be to chronicle their lives and share with friends and relatives, but it could also be because they are part of (online) communities where sharing these photos is part of the shared lifestyle and identity (Blum-Ross & Livingstone 2017, 113).

For some, it is a way to express their creativity and this might also lead to some parents gaining financial benefits from doing so, if they are, for example, bloggers incorporating advertisements or sponsored content on their channels.

Recently, the topic became much discussed in the US after actress Gwyneth Paltrow posted a picture on Instagram in late March of her and her 14-year-old daughter Apple Martin skiing. Apple then responded in the comments sections, saying: “Mom, we have discussed this. You may not post anything without my consent.” The incident sparked discussions on children’s privacy on social media.

Whose Choice Is It?

In China, there is not just a word for ‘sharenting,’ there is even a word to describe parents who ‘sharent’ like crazy: Shàiwá Kuángmó (晒娃狂魔), meaning something like ‘Sharenting Crazy Devils.’

The phenomenon of sharenting was discussed in Chinese media as early as 2012, when it was mostly the safety issue of ‘sharenting’ that was highlighted: with parents posting photos of their children, along with a lot of personal information, they might unknowingly expose their children to child traffickers, who will easily find out through social media where a child goes to school, and when their parents take them to the park to play.

Recently, discussions on sharenting in China have mainly focused on WeChat as a platform where parents not just post photos of their children, but also post about their school results, their class rankings, and other detailed information. Especially during holidays, WeChat starts flooding with photos of children.

Image via Sina.com

Chinese educational expert Tang Yinghong (唐映红) commented on the issue in a news report by Pear Video, saying that sharenting is a sign of parents missing a certain sense of meaning in their own lives, and letting their children make up for this. Regularly posting about their children’s lives and activities allegedly gives them a certain value, status, and identity.

That they are infringing on the privacy of their children by doing so, Tang argues, is something that a lot of Chinese parents do not even consider. Only if the children agree with their parents sharing their photos, he says, it is okay to do so.

But the majority of commenters do not agree with Tang’s views at all. “So what else are we supposed to post in our ‘Moments’? If we post about our kids, it’s sharenting. If we post about our travels, it’s flaunting wealth. If we post selfies, it’s vanity. We should be free to post what we want in our Moments.”

“Showing off our kids is our own choice, if you don’t want to see it, just block it,” others say.

“He’s not right in what he says. I regularly post my child’s picture. My career is going well and I am happy. The goal of me posting these photos is to keep my WeChat Moments feed alive, and I use it as some sort of photo album,” another Weibo user says.

Some voices do agree with Tang, saying: “First ask your children for permission, they also have their right to privacy.”

Kids’ Rights to Privacy

But what if the children are too young to give permission? And from what age are they able to really give their consent? The idea of children’s ‘right to privacy’ is a fairly new one in Chinese debates on sharenting. In other countries, these discussions started years ago.

In the Netherlands, sociologists Martje van Ankeren and Katusha Sol argued in a 2011 newspaper article that parents posting photos of their babies and young children on social media are actually infringing on the privacy of their kids, disregarding what sharing the lives of their offspring online might mean for them in the future, just for scoring a few ‘likes’ on Facebook.

The online presence of children often starts from the day they are born now, building throughout their whole childhood. A 2017 UK news article suggested that the average parent shares almost 1,500 images of their child online before their fifth birthday. The baby’s first steps, medical issues, ‘funny’ photos and videos of a child with food smeared all over its face – it’s all out there. But what happens to all these online records?

Van Ankeren and Sol argue that the social media presence of children might affect them in the future. What if they are applying for their dream job, but their potential future employee finds out through online research that they had serious health issues as a child? And how do young adults feel about their new friends and acquaintances being able to view all those embarrassing photos of them as a child that their parents ‘tagged’ them in from before they could even remember?

“Everyone should have the right to choose what kind of information they want to share, and with whom. If your parents already did that for you, you lost your freedom of choice before you were even able to consider it,” Van Ankeren and Sol write.

The case of France made headlines last year, as its privacy laws make it possible for grown-up children to sue their parents for posting photos of them on social networks without their consent, which could potentially result in hefty fines or imprisonment.

In China, the debate on kids’ rights to privacy is not yet gaining much attention within the ‘sharenting’ discussions. Some people, however, do speak out about the issue on social media.

“I understand you want to share pictures of your child on ‘Moments’,” one Weibo user (@寒月之瞳) writes: “However, why do you insist on [also] sharing nude photos of your child? Small kids are also people, they have a right to privacy. The people on your ‘Moments’ are not all people you know very well. Do you really think it’s a good idea to share these photos?”

An article in the Chinese Baby Sina outlet writes: “Parents have to protect the privacy of their kids, before posting a photo of them on the internet, think about how it might influence them.”

For most commenters on Chinese social media, however, posting pictures of their children online is just an innocent pastime: “I post on WeChat Moments every day. If it’s not photos of my child, I post about the dinner I cooked or the parties I attend. WeChat Moments is about sharing your life, and in my life, my child is what matters most. It’s only natural that most of my photos are of my child.”

“People shouldn’t meddle in other’s people’s business. Whether or not I want to post my child’s photos is up to me.”

By Manya Koetse

References

Blum-Ross, Alicia and Sonia Livingstone. 2017. “”Sharenting,” Parent Blogging, and the Boundaries of the Digital Self.” Popular Communication 15 (2): 110-125.

Van Ankeren, Martje and Katusha Sol. 2011. “Willempje wil geen Facebookpagina.” Nov 2, NRC: 12.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

The post ‘Sharenting’ on Chinese Social Media: When Parents Are Posting Too Many Baby Pics on WeChat appeared first on What's on Weibo.