By Manya Koetse, with contributions from Miranda Barnes

The tragic story of a young Tibetan woman named Lamu (拉姆, Lhamo in Tibetan) is going insanely viral on Chinese social media these days, triggering massive outrage over the problem of domestic violence in China.

Update: also listen to our podcast on this story here

With over 700,000 followers on the Chinese video app Douyin, Lamu was popular for doing short videos about her life in the countryside since 2018. Singing, dancing, cooking, and showing fans the nature in her mountainous hometown, she was admired for her natural beauty and energetic attitude.

'Lamu' was popular on Douyin for singing, dancing, cooking, and showing fans the nature in her mountainous hometown. Fans praised her for showing the sunny side of her simple life. pic.twitter.com/YtlFHiGbsK

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) October 7, 2020

The 30-year-old lived in the Guanyinqiao town of Jinchuan County, at the edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Living in poverty, Lamu worked hard to make some money. Her videos showed the dirt on her clothes and her poor living conditions. Fans praised her for showing the sunny side of her simple life.

Lamu’s videos on Douyin (screenshot via whatsonweibo.com).

But Lamu’s personal circumstances were nowhere near as sunny as they appeared in her videos. For years, the mother of two experienced severe domestic abuse by her husband, Tang X. (唐某).

Lamu divorced Tang, after which they both gained custody over one child. But the abuse continued as the ex-husband threatened to kill one child if Lamu would not get back together with him.

Several news sources describe how Lamu reported the abuse to the police multiple times, but that no action was taken – local officers deemed the case a ‘family matter.’

Afraid for the safety of her child, Lamu was pressured into remarrying her ex-husband. But after recurring abuse and afraid for her own life, she again divorced him earlier this year. A local court ruled that Tang, who had more financial resources, would get custody over both children.

Things took a turn for the worse in September of this year, when Tang burst into Lamu’s home. Lamu was stabbed, doused in gasoline, and set on fire by her ex-husband on the night of September 14, while she was trying to livestream from her home.

With 90% of her body damaged by flames, she was transported to Sichuan People’s Hospital where she eventually succumbed to her injuries on September 30. Tang X. has since been detained while the case is under investigation.

The story gained widespread attention on social media platforms Douyin and Weibo, and soon went viral, although some hashtags and topics related to the news were censored later on.

One of the most-read in-depth online blogs about Lamu is that by ‘Guyu’ (谷雨) titled “Lamu, Burned by her Ex-Husband” (“被前夫烧毁的拉姆”). The article explains more about Lamu’s low-income, low-education background, her struggles to take care of her sick father, and her hard work to generate money for her family.

Lamu’s sister Zhuoma (卓玛, Dolma in Tibetan) posted a social media video on October 1st in which she tearfully shared the tragic news: “Yesterday, my younger sister has left us forever, (..), but she will always remain in our hearts.”

Lamu’s sister thanked Chinese netizens for their support.

Zhuoma also thanked social media users for their support. In an effort to help pay for Lamu’s medical costs shortly after her hospitalization, fans set up an online crowdfunding campaign for her and were able to raise over 1 million yuan ($150,000) within a time frame of just seven hours.

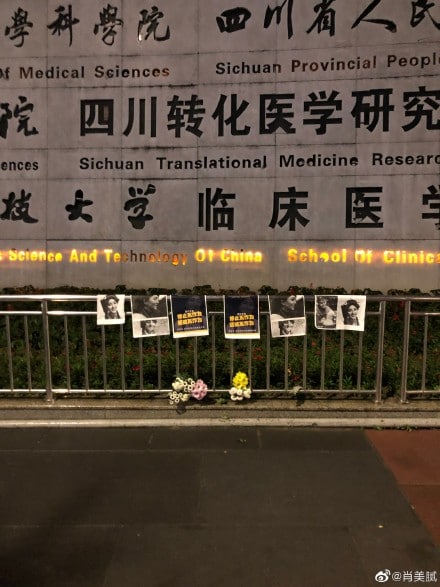

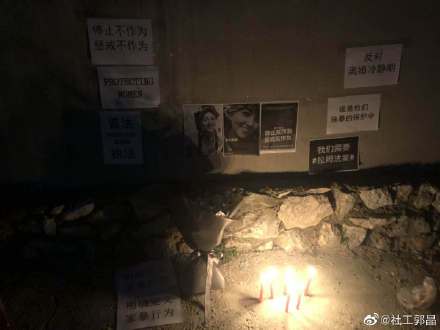

A memorial for Lamu after her death, posted on Weibo.

Lamu’s funeral was held at a local temple on October 5. The hashtag “Lamu is Cremated Today” (#拉姆今日火化#) received over 310 million views on Weibo.

“Domestic violence is not a family issue!”

In the wake of Lamu’s death, and despite censorship, Chinese netizens started speaking out against domestic violence, advocating for better laws and support systems for domestic abuse victims in China.

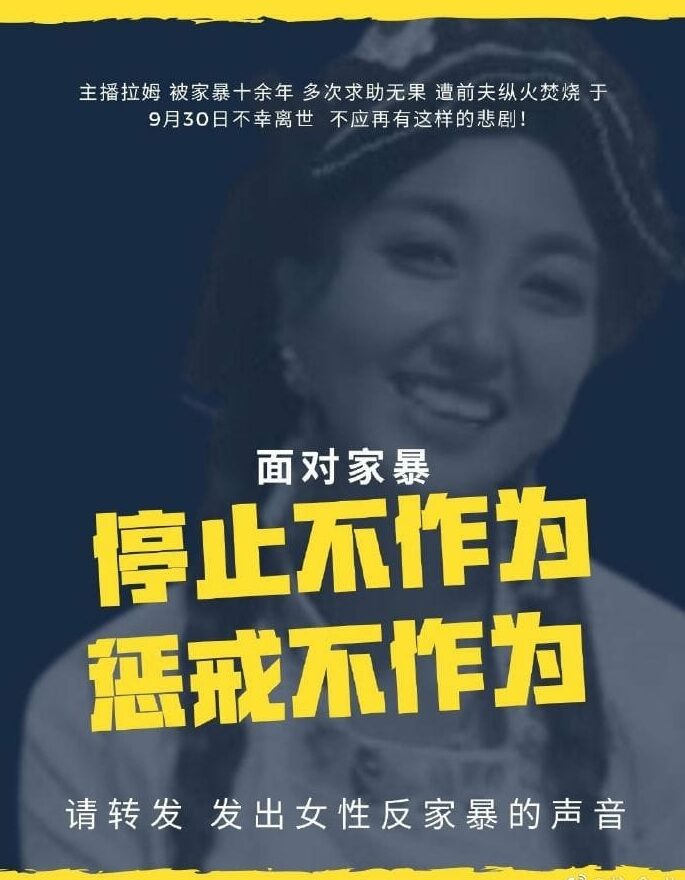

An online poster that was shared online by hundreds of netizens says:

“Vlogger Lamu suffered domestic abuse for over ten years. She reached out for help many times to no avail. She was burnt by her ex-husband and died on September 30th. We can’t let this kind of tragedy happen again! Let’s confront a lack of action in the face of domestic violence, inaction should be punished. Please forward and make women’s voices against domestic violence heard!”

Chinese actress Li Bingbing (李冰冰) also spoke out about the matter on Weibo, saying: “Don’t be indifferent, don’t stay silent, domestic violence is not a family matter, it is a crime!”

Many raising their voice against domestic violence mention how Lamu’s case, unfortunately, is not unique. There have been similar cases before, and there are millions suffering behind closed doors. A 2016 survey by the All-China Women’s Federation estimated that 30% of married Chinese women had experienced some form of domestic violence.

Domestic abuse was officially criminalized with China’s first national law against domestic violence in 2016, but it is still a widespread problem, partly due to a general lack of public awareness of domestic abuse and police officers regarding it as a private family matter, downplaying its severity.

Another issue is how the legal repercussions for the perpetrators of domestic violence are often mild or even non-existent.

As noted by author Hao Yang in this article, the Chinese law’s definition of domestic violence covers physical and psychological violence, yet does not explicitly include sexual violence such as marital rape. The law also does not include violence against former spouses or partners who do not live together.

There is also no clear national implementation guideline for China’s Domestic Violence Law, and no standard procedure for protecting victims.

Lamu’s death has stirred online discussions on the importance of addressing all of these aforementioned problems. These kinds of online discussions on domestic violence have risen before, but the voices have rarely been as loud as they are now.

“Domestic violence is the most frightening and harmful type of violence since it comes from within one’s own family. If the police are useless, then how can women ever protect themselves?”, one Weibo commenter writes, with another person responding: “Domestic violence is not a family issue! I hope the relevant authorities will start paying more attention to this!”

“We need a ‘Lamu Bill'”

One popular Weibo user, a screenwriter from Beijing with approximately 240,000 followers, argues that the intervention of authorities in domestic abuse cases is sometimes literally a matter of life and death.

“Women who are victims of domestic violence should not have only two destinies,” the blogger writes: “..either being beaten to death or struggling to kill.”

This blogger, along with other social media users, also mentions other cases where the non-intervention of local authorities in domestic abuse cases led to a tragic ending.

Two of the cases often mentioned together with Lamu’s case are that of Dong Shanshan (董珊珊), Li Yan (李彦), and Ms. Liu (刘女士).

Dong Shanshan was a 26-year-old woman from Beijing who suffered abuse from her husband shortly after getting married. Dong and her family reported the abuse to the police a total of 8 times, but the police allegedly were reluctant to intervene in something that was deemed a “family dispute.” After another beating by her husband, Dong died of internal organ failure in 2009. Her husband was sentenced to six years in prison.

Dong Shanshan

Li Yan suffered abuse by her husband Tan Yong ever since they got married in 2009. Although Li reported the abuse to the local justice department, police, and the All-China Women’s Federation, local authorities did not intervene. When the abuse got worse – including Tan hitting Li’s head against the wall, hacking off one of her fingers, and stubbing out cigarettes on her face and body, – Li (accidentally) killed her drunken husband with a gun barrel after he threatened to shoot her. Li was sentenced to death in 2011. The sentence was overturned in 2015 and commuted to life in prison.

Ms. Liu‘s case made headlines after the woman from Henan jumped from a second-story window to escape domestic violence. Footage of Liu landing on the street – a fall that left her temporarily paralyzed – went viral earlier this year when it became known that Liu had filed for divorce but this was denied by a local court. The court reportedly denied Liu’s petition for divorce due to her husband’s unwillingness to separate, and because her claims of domestic violence could not be verified without a criminal complaint. In the summer of 2020, Liu was finally granted a divorce.

A law that was released in 2020 introduced a mandatory “cooling off period” of thirty days after couples file for divorce. The law is allegedly intended to make people think twice before officially separating, but it also triggered public outrage for making victims of domestic violence even more vulnerable.

Lamu

In light of Lamu’s case, many people on Weibo and Douyin now support a so-called ‘Lamu Bill’ (拉姆法案), that should legally empower victims of domestic abuse, more so than the current law on domestic abuse does.

Netizens suggest it should include the automatic dissolution of a marriage once one side wants a divorce for one’s own personal safety, and that it should criminalize marital rape.

“We need the ‘Lamu Bill’, we can’t let these kinds of cases happen again,” multiple commenters say, with others also writing “if you don’t speak up, nothing will ever change.” One post on the issue received over 630,000 likes.

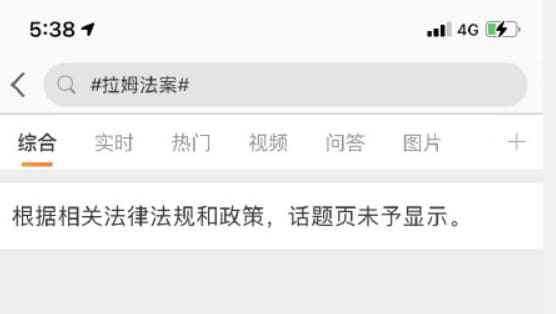

On Weibo, the hashtag page for the topic has now been taken offline and many people note that the topic has been taken down from Weibo hot search lists.

At the time of writing, the hashtag “Stop Nonfeasance” (#停止不作为#), that is also used to call for change and better enforcement of China’s domestic violence laws, is still open on Weibo and Douyin. On Douyin, many netizens speak out against domestic violence via video; on Weibo, they do so via posts and images.

Multiple images and videos show that the online movement against domestic violence also takes place offline, with people creating small memorials outside and leaving the “Stop Inaction” posters outside the Sichuan hospital.

Besides the censored hashtag and the “Stop Nonfeasance” hashtag, there are also other terms and hashtags used by Weibo and Douyin users to get their message across.

Lamu’s story is passed on and has become much bigger than her tragic death alone. “I could be Lamu,” some female commenters say.

“When people stay silent, women have no way to speak up,” one person writes. And so, through online and offline memorials, posters, hashtags, and photos, the calls for action against domestic violence are everywhere. Even in the face of censorship, many social media users seem determined to make their voices heard.

By Manya Koetse , with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2020 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

The post Justice for Lamu: Death of Tibetan Vlogger Sparks Online Movement against Domestic Violence appeared first on What's on Weibo.